2324 Lance-Naik Indar Singh IDSM : 36th Sikhs

By : Avtar

Singh Bahra, Kulwant Singh Bahra & Dalwinder Singh Sidhu

On

the 28 February 2018, an auction house sold an Indian Distinguished Service

Medal awarded to Lance-Naik Indar Singh.

The catalogue description of the medal was “Indian Distinguished Service Medal, G.V.R., 1st issue (2324 Lce Naik Indar Singh 36th Sikhs)”. A

footnote recorded that the notification of the award appeared in G.G.O. 1386 of

1916 (dated 18 November 1916) and the award was for Mesopotamia. The medal’s

condition was recorded as “good very fine” and it was given an estimate of

between £300-360. The estimate was far

too low considering the prices Sikh gallantry medals have commanded, especially

when they are awarded to soldiers serving in Sikh regiments, in recent years.

The medal was hammered for £2000 without commission.

While

I haven’t been able to find a citation for Indar Singh’s medal, I have been

able to work out when he joined the 36th Sikhs. He was a career

Indian Army soldier and was one of the longest-serving

men of the Regiment when he was awarded his IDSM. I have used a variety of

sources to build up a history of the 36th Sikhs before the outbreak

of war, so you know where Indar served. As I will show, I believe that Indar

was very likely awarded his IDSM for gallantry on 12 April 1916 during an

attack on the Turkish position near Beit Assa. This was during the Kut-al-Amara

relief attempts.

Researching

soldiers who served in the Indian Army during the First World War is a

difficult task. Not only have service and medal records been lost but there are

usually no biographical sources to add more information about a soldier. The

only information I have had to work from for Indar was impressed around his

IDSM and the date the medal was announced. The Indian Army had no unique

regimental numbers during this period. If a soldier joined a regiment they

received a regimental number which was only unique within that regiment. If

they were transferred to a new regiment, they received a new number. The

numbering of Indian infantry regiment pre-war was straightforward and

chronological. Each new man joining the regiment received the next number and

when the regiment hit a number around 5000 it reset back to 1.

Indar’s regimental number of 2324 dates to early 1901 for the 36th

Sikhs. It is possible he enlisted in a different regiment and transferred to

the 36th Sikhs but most soldiers remained in a single regiment, at

least pre-war. As most Indian soldiers enlisted around the age of 16 – 20, I

expect he was born in the early 1880s and was in his thirties on the outbreak

of the First World War. Another soldier of the Regiment, 2240 Dall Singh IDSM

enlisted on 17 June 1900. I have looked at soldiers of the 36th

Sikhs who were awarded Long Service and Good Conduct Medals with the

announcements of the award appearing in a variety of Indian Army Orders. While

dating from the period prior to Dall Singh’s enlistment (there is a long gap

caused by casualties sustained during the First World War) they support 2324

being an early 1901 date.

In

addition, seven soldiers were awarded the IDSM serving with the 36th

Sikhs during the war had a regimental number between 2100 and 2400. Of these,

four were Havildars and two Naiks, further supporting the view that Indar’s

date of joining the Regiment was early 1901. Due to this date, I consider that

it would have been very unlikely that Indar was a Reservist called back to the Colors

on the outbreak of war. A soldier completing his terms of enlistment in the

Indian Army did not have to complete a period in the Reserve as in the British Army. Also, Indar served into

the early 1920s before he left the Indian Army which is another indication that

he was a career soldier.

The

36th Sikhs had initially been raised as the Bareilly Levy in May

1858, one of several Sikh regiments formed in consequence of the Indian Mutiny

(1857 – 1858). The Regiment designation changed twice in 1861, becoming first

the 40th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry and subsequently the 36th

Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry. The Regiment’s designation changed to the

36th (Bareilly) Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry in 1864 and it

was disbanded in 1882. The Regiment was raised once again in 1887 at Jullundur

(Jalandhar, Punjab) by then Lieutenant-Colonel, later Major-General, James

Cook. James Cook used to travel the Punjab

looking for prospective recruits and challenge them to wrestling matches.

The

Regiment’s new title was 36th (Sikh) Regiment of Bengal Infantry and

it was a class regiment composed solely of Sikhs. This changed in the years

after the First World War when Punjabi Muslims were enlisted. In 1901, the

Regiment became the 36th Sikh Infantry and then the 36th

Sikhs in 1903. In 1922, the Regiment became the 3rd

Battalion 11th Sikh Regiment. The regimental center was at

Rawalpindi (Punjab, Pakistan) and it was linked to the 35th and 47th

Sikhs.

The

Regiment saw service on the North West Frontier (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan) during the

1890s. The most common pre-war medal for soldiers of the Regiment is the India

Medal (1895 – 1902) with a combination of the following clasps: Punjab Frontier

1897-98, Samana 1897, and Tirah 1897-98. Small numbers of the 36th

Sikhs also qualified for the Central Africa 1891-98 medal. The Regiment had

found fame during the Battle of Saragari on 12 September 1897 during the Tirah

Campaign. A small fort garrisoned by 21 soldiers of the Regiment fought to the

death against overwhelming odds with all the soldiers receiving the Indian

Order of Merit.

The

most important source of information regarding the Regiment pre-war is the 36th

Sikhs’ confidential reports. These reports were published annually and included

the confidential reports of British officers serving with the regiments. They

are held at the British Library in Collection 405: Confidential Reports of

Regiments etc. (1887 – 1939): IOR/L/MIL/17007-17037. Unfortunately, the earlier

and post-1920 reports aren’t of the same

format as the examples I have provided for you. I have included a set of reports

for the period between 1902-03 and 1919-20. There were no reports for the years

1914-15 and 1915-16 (common for the first years of the war) and the other

surviving war reports are for the unit’s Depot.

After

a long period on the North West Frontier, the 36th Sikhs arrived at

Rawalpindi on 7 May 1898. The Regiment remained in the city until it moved to

Malakand, North West Frontier Province on 25 September 1901. It was at

Malakand, that Indar joined the Regiment. Indar would have trained at Meean

Meer (Lahore Cantonment) where the 36th Sikhs’ Depot was located.

The Malakand region was in

the northeast of India running along the

Afghan border. There had been fighting at Malakand in 1897 with a siege and a

field force being despatched. The events are chiefly remembered these days for

the involvement of a young Winston Churchill who joined the field force as a

war correspondent for the Daily Telegraph

and subsequently published The Story of

the Malakand Field Force.

I

have only quoted parts of the Regiment’s confidential reports below. In its

report for 1902-03, Major-General C. C. Egerton, Commanding Punjab Frontier

Force and Frontier District wrote:

Personnel: The British Officers are

keen, smart, and all take the greatest interest in their work. The Native

Officers are well selected and efficient. The rank and file are a magnificent

body of men.

Drill and Instruction: Very steady on parade,

handle their arms smartly, and work very

well in field maneuvers. They have benefitted greatly by their local surroundings, which afford great opportunities for

training in hill warfare.

General condition: (a) The Battalion is in first rate order. (b) Well trained in the field

and in practical musketry. (c) In all respects fit for service.

The

Regiment received another good report for 1903-04 with its personnel described

as “A magnificent regiment of fine physique”. The Regiment, at least during its

early years, had a minimum height standard of 5 foot 8 inches (1.73 m). The

report was highly favorable to the 36th Sikhs. The next year’s

report stated that also praised the Regiment with its personnel reported as “A

very fine regiment above the average in physique. Rather a superior body of

officers”. On the 6 January 1904, the Regiment arrived at Peshawar, the capital

of the North West Frontier. Due to the turbulent nature of the North West

Frontier and the city’s location close to the Khyber Pass linking India to

Afghanistan, the city held a large garrison.

The

36th Sikhs remained at Peshawar for nearly

three years, before it arrived at its regimental center of Rawalpindi on 3

December 1906. The Regiment continued to receive excellent reports during its

stay Peshawar, with its personnel described in its 1905-06 report as “A very

fine regiment with good British Officers and a good tone throughout”. The 36th

Sikhs’ was inspected by Brigadier-General C. H. Powell, Commanding Rawalpindi

Brigade for 1907-08:

Personnel: Is up to modern standard

and on the whole very satisfactory.

Efficiency in Drill: Drill and instruction is very satisfactory in all its branches. The

training of recruits receives special attention.

General Efficiency: Smart and soldier like and

most ably commanded. The individuality and independence of action of all ranks is properly encouraged: there is no tendency to

over-centralization. In all respects fit for active service.

Major-General

J. Stratford Collins commanding 2nd (Rawalpindi) Division reported:

Well commanded and particularly well efficient

regiment. There is a very good tone in all ranks. Their turn out is very good

and there is considerable esprit de corps.

Fit for active service. In much the same state as last year.

In

its final confidential report at Rawalpindi, the Regiment was described as “An

Indian regiment it is a pleasure to look at, the men of excellent physique are

turned out, well set up, and smart in appearance. The Native officers are a

particularly nice body of men”. On the 12 March 1911, the Regiment arrived at

Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh, India) and this was the 36th Sikhs’ last station

in India pre-war. The last surviving confidential report for the Regiment

pre-war, 1912-13, dates from its service at Lucknow. Lieutenant General Sir

Robert Irvin Scallon, Commanding 8th (Lucknow) Division reported

that the 36th Sikhs was “An excellent battalion, fit for war”.

The

Regiment left India in 1914 and arrived at Tientsin, North China on 27 May 1914

where it was still stationed on the outbreak of war. Tientsin, now Tianjin, is 70

miles southeast of Beijing. While in China, the 36th Sikhs had detachments

at Shan-hai-kuan and Chin-Wang-Tao.

Chin-Wang-Tao is now Qinhuangdao a port city in northeastern China, 159 miles

northeast of Tientsin. Shan-hai-kuan

(Shanhaiguan) is now part of the port city of Qinhuangdao. While in China, the

Regiment’s Depot was at Fatehgarh (Uttar Pradesh). In the aftermath of the

Boxer Rebellion (1899 – 1901), Britain increased its garrison in China, with

Indian soldiers often being used.

On

the outbreak of war, the 36th Sikhs was

still at Tientsin and it was fortunate that it was. If it had been in India, it

would almost certainly have been sent abroad as part of one of the Indian

Expeditionary Forces. Even if it had remained in India, it would have sent

large drafts of men to other regiments. In the end, the only drafts it sent to

other regiments, including the 14th and 47th Sikhs were

mostly composed of new recruits who were trained at the Regiment’s Depot in

India. The Regiment’s first action during the war was at the Siege of Tsingtao

which had been blockaded on 27 August 1914. Tsingtao, now Qingdao was part of

Germany’s Kiautschou Bay Concession and was 360 miles southeast of Tientsin.

An

Anglo-Indian force consisting of the 2nd Battalion South Wales

Borderers and half the 36th Sikhs was sent to join the Japanese in

the siege. The 36th Sikhs arrived in late October 1914 with land

operations beginning on 31 October and ending on 7 November 1914. The

Anglo-Indian soldiers were just a token

force sent to help the Japanese and the 36th Sikhs suffered 2 dead

during the operations. If Indar was one of the soldiers sent to Tsingtao, he

would have qualified for the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal.

The 36th Sikhs did not remain at Tsingtao for long after the end of

the siege before it rejoined the rest of the Regiment at Tientsin.

A

detachment of the Regiment was sent to Singapore at some point early in the war

and was present when the 5th Jat Light Infantry mutinied February

1915. However, at the start of the mutiny,

it was without arms or ammunition. At some point between February and August

1915, the Regiment returned to India and proceeded to the North West Frontier.

The 36th Sikhs took part in the Battle of Shabkadar, near

Peshawar on 5 September 1915, against Mohmand tribesman. This was the largest

battle fought on the North West Frontier since 1897 and the Regiment suffered

four dead. The Regiment saw further fighting on the 17 September when another

four soldiers were killed. If Indar took part in the operations with the

Regiment, he would have qualified for the 1914-15 Star, he definitely qualified

for the British War Medal and Victory Medal.

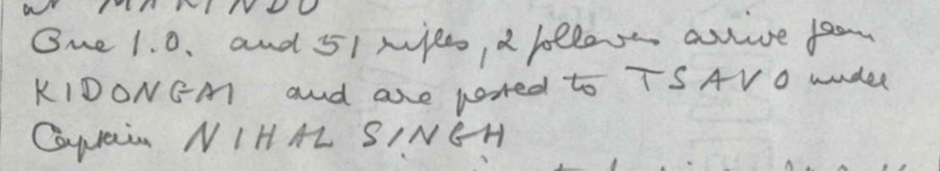

I’m

not sure of the 36th Sikhs’ location between October 1915 and

February 1916 but I expect it was somewhere on the North West Frontier or

nearby. The Regiment’s war diary doesn’t start until the 1 March 1916 when the unit

was in camp at Basra, Mesopotamia (Iraq). I expect that the Regiment left India

in late February 1916, probably at Karachi. With the 36th Sikhs

arrival in Mesopotamia we can return once again to Indar as he was one of the

men who was camped at Basra.

The

announcement of Indar Singh’s award of the Indian Distinguished Service Medal

was published in Government General Orders 1386/1916 (dated 18 November 1916).

The medal was awarded for gallantry in Mesopotamia. I have looked at other

Indian soldiers awarded the IDSM in G.G.O. 1386/1916 and the awards were for

the attempts to relieve the besieged 6th (Poona) Division at

Kut-al-Amara. The 36th Sikhs was

part of the 37th Indian Infantry Brigade, 14th Indian

Division when Indar won the medal. There had already been three battles to try

and break the siege, the Battle of Sheikh Sa’ad (6 – 8 January 1916), Battle of

Wadi (13 January 1916) and Battle of Hanna (21 January 1916). While these

battles had pushed back the Turkish forces, the Anglo-Indian force had suffered

heavy casualties. I have included the following maps of the area Indar won his

IDSM as it’s very difficult to follow the battles without them:

·

Part of map T.C.4. “which had been issued to the troops prior

to the 6th March 1916”

·

To illustrate operations between 10th March &

end of April 1916

·

The Attack on the Dujaila Redoubt 8th March 1916

These

were taken from Official History of the

War: Mesopotamia Campaign: Volume II.

I have also included a modern satellite image of the area and you can

clearly see the Dujaila Depression.

The

Regiment left Basra by boat on 2 March and proceeded up the Tigris to join the

fight. The Regiment reached Wadi Camp, past Shaikh Saad on 7 March where “two

shots were fired at the ship during the night without result, probably by an

Arab sniper on the bank”. The Battalion disembarked the next day and moved to

the “Ruined Hut Position map T.C.4. Square 16/D”. This was about 5 miles

southeast of Beit Isa as the crow flies. There are some interesting entries in

the war diary for the remainder of the month, including the appearance of

“large bodies of Arab horseman” around the camp on 10 March. Also, flooding on

the 16 March. The Regiment spent the month to the north and northeast of Umm al

Baram, the marshy ground shown on the maps. There is nothing recorded in the

war diary between 7 March and 11 April 1916 to suggest any gallantry medals

were awarded in this period.

The

most likely date for Indar Singh’s act of gallantry was on the 12 April 1916

when an attack was made on the Turkish trenches near Beit Isa. I have

photographed the relevant section of the official history and there is a

detailed description in the war diary. The 36th Sikhs was in newly dug trenches west of the Abu

Rumman Mounds. I have quoted from the war diary of the 27th Indian

Infantry Brigade Headquarters below, as it gives the clearest indication of

what happened:

12 April 1916: 3 pm: Orders received for the 37th

Brigade acting in conjunction with 8th and 7th Brigades

to push forward and drive in enemy picquets and to establish strong picquet on

line 18C 4/0 to 18C 5/6 said to be held by enemy picquets. Instructions issued

to this effect at 3 pm for 1/4th Somersets and 36th Sikhs

to advance with 8th Brigade on their right. 36th Sikhs to

maintain touch with 7th Brigade who were south of flooded area. 1/2nd Gurkhas being

kept in reserve.

3.30 pm: Advance commenced 3.30 pm and was soon

heavily opposed, especially in front of 36th Sikhs, who came under

machinegun fire. Water in some cases over 2 feet deep also hampered the

advance.

7 pm: About 7 pm one Double Company 1/2nd

Gurkhas was pushed up to reinforce 36th Sikhs and assist them in

continuing the line to the left. About 11 pm a second Double Company 1/2nd

Gurkhas was pushed up as information was received that 36th Sikhs

had suffered severely. Early in the evening telephone communication with 36th

Sikhs had broken down and all messages had to be sent by hand which again were

further delayed by darkness and water. As far as could be ascertained in the

darkness the line ordered was occupied by 36th Sikhs with 1/4th

Somersets on right and 59th

Rifles on their right from about 7 pm.

About 9.30 pm 8th Brigade reported that

owing to water 59th Rifles and Manchesters were consolidating their

position about the line where their advance picquet was before operation commenced and that it was not

possible to dig in further westwards owing to subsoil water. Units were so

informed: 1/4th Somersets being instructed to keep in touch with 59th

Rifles and not to lose touch with 36th Sikhs. About 1 am on 13th

1/4th Somersets informed they had had to fall back to maintain touch

with 59th Rifles.

36th Sikhs had accordingly to fall back to line about 600 – 800 yards in rear as no intermediate line could be found

owing to water. A line was accordingly established from 18D 60//15 through

18D/80/50 to edge of flooded area near

the Narrows (Divisional Sheet 16). About 8 pm Brigade Headquarters moved

forward to trenches from which ¼th Somersets originally moved.

The

36th Sikhs casualties were recorded as one officer killed and three

wounded, 34 other ranks killed, 144 wounded and 13 missing. The Commonwealth

War Graves Commission (CWGC) recorded a total of 45 dead for the 36th

Sikhs on 12 April 1916 with all of them commemorated on the Basra Memorial to

the missing. The Regiment’s strength on 13 April was recorded as 7 British

officers, 7 Indian officers and 341 other ranks. While there was an assault on

the Beit Isa on 17 April, the 37th Brigade was held in reserve,

though it did suffer 20 casualties from shell fire. On the 29 April, the 6th

(Poona) Division surrendered at Kut which was noted in the Regiment’s war diary

on 1 May. Without a surviving service record its impossible to know if Indar

became a casualty or was invalided from the Regiment later. So, I’ve provided

an overview of the 36th Sikhs’ activities during the remainder of

the war.

For

the rest of the year, very little occurred in the Mesopotamia Campaign. Summer

brought a lull in the fighting as the Anglo-Indian forces were reorganized.

Between 1 May and 31 December 1916, the CWGC recorded a total of 10 dead for

the 36th Sikh. At least 2 died from accidents and some would also

have been from disease. I have checked

the war diary for the rest of the year and there are no incidents recorded

which suggest a gallantry award would be made for them. Of 19 IDSM awards for

the 36th Sikhs during the First World War, seven appeared in G.G.O.

1386 of 1916 (dated 18 November 1916) and three in G.G.O. 1388 of 1916 (also

dated 18 November 1916).

The

Regiment took part in the Anglo-Indian offensive which began in December 1916.

However, they were only to fight in one more battle during the war. This was an

unsuccessful attack on a Turkish position to the south of Kut. I have included

another map in the folder: Map to Illustrate Operations against the Hai Salient

and the Dahra Bend Positions and the Passage of the Tigris: 11 January – 24

February 1917. The 37th Brigade advanced from a line of trenches

from P13 A on the bank of the Shatt-al-Hair River to P16 (Gunning Trench). This

area is approximately 1.5 miles southwest of Kut as the crow flies.

The

official history recorded:

The operations on the west of the Hai were not so

successful, owing partly to the fact that the British preliminary preparations

had not been quite completed, especially in regard to work on the communication

trenches. After ten minutes’ intense artillery bombardment, the 45th

and 36th Sikhs of the 37th Brigade advanced to the

assault at 12.10 p.m., the 45th moving on the right in eight waves

and the 36th in four waves, on frontages of two hundred and sixty

yards and two hundred yards respectively. Immediately on emerging from the front

line trench, both battalions came under very heavy enfilade artillery and

machine gun fire from the northwest and from their left front.

The 45th managed without great loss to

capture both the first and second Turkish lines of trench; but the 36th, being more exposed, suffered such

heavy losses that in spite of most gallant efforts they could get no farther than the enemy’s first line, which they

found only lightly held.

The Turks then launched against both battalions a

heavy counter-attack which the advanced portions of the 45th Sikhs

tried to repel as it got to close quarters by a gallant charge across the open.

But although they, the 36th Sikhs and our supporting artillery

caused the enemy severe losses, the 45th also suffered very heavily;

and overweighed by numbers the remnants of both Sikh battalions were driven

back by 1.30 p.m. to their original starting point.

Out of a total of 17 British officers, 30 Indian

officers and 1,280 other ranks actually engaged in the two battalions, 16

British officers, 28 Indian officers and 988 other ranks had become casualties.

These casualties speak for themselves.

The

Regiment’s war diary recorded that after the battle “the Regiment now totaled 3

British officers, one of whom was wounded, one Indian officer and 85 men”. The

war diary also recorded that the 36th Sikhs went into the attack

with 10 British officers, 15 Indian officers and 618 other ranks. It suffered

the following casualties:

·

British officers: 4 killed, 1 died of wounds, 1 missing

believed killed and 3 wounded

·

Indian officers: 3 killed and 11 wounded

·

Other ranks: 71 killed, 54 missing and 388 wounded

This

was a casualty rate of 83% of those who took part in the battle and the

Regiment had to be withdrawn from the front to reorganize and await the arrival

of new drafts. What was left of the 36th Sikhs was used on the

Tigris Defences and Lines of Communications for the rest of 1917. During this

entire period, the Regiment was at Amara. Between February and August 1918, the

Regiment worked on the lines of communications at around Baqubah. Baqubah is a

city 30 miles north of Baghdad and there was nothing to report for this period.

In

September 1918, the Regiment left Baqubah to move to Persia where it joined the

North Persia Force and joined the 36th Infantry Brigade. The 36th

Sikhs arrived at Hamadan, 200 miles southwest of Tehran on 6 October. The

Regiment remained at the city until May 1919 when it moved back to Mesopotamia.

There is very little to report regarding the 36th Sikhs’ stay at

Hamadan. In Mesopotamia, the Regiment garrisoned Kut-al-Amara as it was now

back on garrison and line of communication duties. The Regiment’s war diary

recorded on 30 September 1919 that “orders received that Regiment would embark

at Busra [Basra] for India on 9 October 1919 in the [?] and would be relieved

at Kut by 1/6 Gurkhas”.

The

36th Sikhs’ Depot had been at Bareilly (Uttar Pradesh, India) from

around 1918 onwards and once back in India, the Regiment also proceeded there.

However, it wasn’t there for long, as it moved to Nowshera (Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan) around February 1920. Nowshera is 27 miles east of

Peshawar. There is one final confidential report for the Regiment in the old

format by Brigadier-General J. W. O’Dowda, Commanding Nowshera Brigade, dated 9

March 1920:

This battalion has only recently arrived in Nowshera,

and I have not seen much of its field work owing to absence from the Station.

Instruction and Training appears to be

well organised. Drill and manoeuvres satisfactory. The battalion has done no

regular Musketry since leaving Mesopotamia and is engaged in preliminary

instruction to be followed by selected practices. Fire direction and control

require attention. Bayonet instruction good. The battalion has also commenced

regular instruction in Mountain Warfare.

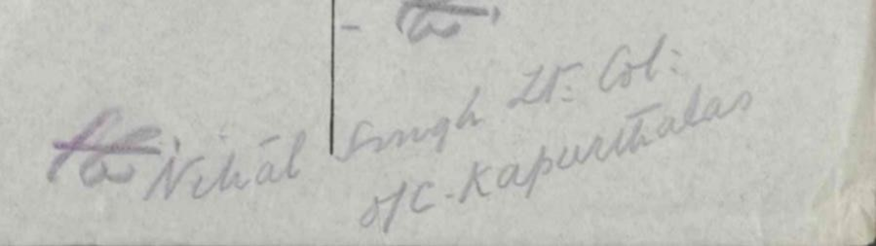

When Indar was awarded the IDSM, he started appearing in

supplements to the Indian Army List

recording Indian soldiers who had been awarded decorations. These supplements

are very useful in tracing gallantry winners as you can work out when a soldier

left the Indian Army when they stop appearing. Indar appeared in the January

1922 Indian Army List but not in the

January 1924 edition. This meant that Indar served for just over 20 years in

the 36th Sikhs before he left the army.

On the 9 February 1921, the 36th Sikhs left

Nowshera for Waziristan. By the 15 February, the Regiment had reached Saidgi (Sidgi), an isolated

posting in North Waziristan close to the Afghan border. Saidgi is 11 miles

northwest of Dande Darpa Khel. As Indar was probably around 40, he may have

left at the Regiment’s Depot at Jhelum. The Regiment was part of 8th

Indian Infantry Brigade and I have included a very short war diary for February

– March 1921. The Regiment qualified for the India General Service Medal

1908-35, with Waziristan 1921-24 clasp for its service on the frontier. The

Regiment remained at Saidgi until early 1923, as it was reported the 36th

Sikhs arrived at Ahmednagar (Maharashtra, India) on 23 April 1923. Indar would have left the Regiment

at some point during this period.

Every medal issued to a Sikh or anybody else has a story

behind it. The story of Lance-Naik Indar Singh of the 36th Sikhs available here

is after pain staking research, time spent, money and being relentless in the

search for the truth. Hopefully this example would be an inspiration to write

many more stories about the other Sikh medal recipients.

This book is the first attempt by anybody to try to compile

medals or medallions issued to Sikh soldiers between 1840’s to 1947. There are

many more military and non-military medals out there issued to Sikhs during

that period which are not recorded in this book. The recipient of all these

medal are well documented or course, but the medals in themselves are very hard

to obtain. Most families of these recipients have ignored these medals and

either have sold them or melted for its silver value and made into jewelry.

The contribution of the Sikhs can only be documented if somebody is willing to spend the time and

money to do it. The Sikh coins issued in the early 18th Century left

a great legacy, up to 1849. I would say this continued even after that , and

was made very visible from the medals issued to these brave Sikh soldiers since

then.